Historical Fiction Research:

Researching My Novel

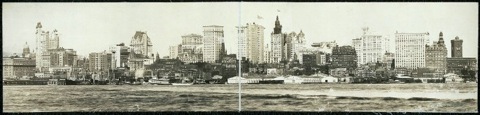

New York City Skyline 1900; Library of Congress,

Prints and Photographs Division (reproduction number LC-USZ62-69028)

For historic pictures of May and the places she traveled, check out my Pinterest Board on Parlor Games.

PARLOR GAMES takes place in the late nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, across wide-ranging locales—from small-town Michigan to New York City, Tokyo, London, and several European sites. The central character, May Dugas, was an adventurous woman who tangled with the Pinkertons while seeking wealth and the high life. So I had to research my protagonist, many locations, life at that period, and the Pinkerton Detectives.

My interest in May Dugas began with the discovery of journalist Lloyd Wendt’s Chicago Daily Tribune 1946-1947 series, Most Dangerous Woman in the World. Mr. Wendt’s account provided the broad outlines and many fascinating details of my protagonist’s life.

I conducted literature searches at and browsed collections of large public and university libraries for books on such topics as prostitution, blackmail, and the Chicago and San Francisco underworlds. As it turned out, many resources address these topics, and I had to sift through them to identify those that were most relevant. Some of the books I had to order via interlibrary loan. Others I could pull off the shelf and peruse before deciding whether they would inform my project. A number of them were so rich in information that I bought them, knowing they would be handy references. I read and skimmed many books, including scholarly works, historical accounts, monographs, novels, and writings from the period.

Photographs and films, both documentary and cinematic, were also very helpful. I was able to find some actual film footage of early 1900s New York, London, Shanghai and Tokyo scenes. Such visual material is invaluable as an aid to scene construction. There is nothing like real-life shots of a place to stimulate the imagination and assist one in conjuring vibrant details.

Period newspapers were a rich source of information. They provided a sense of the language and tenor of the times, as well as detailed information about contemporary events and controversies. I obtained numerous articles from the Menominee Library about May Dugas’s coming and goings, as well as her Menominee trial. I also discovered New York and London accounts of her escapades in those cities.

Language is a living and changing thing. To write about a different era, I needed to obtain a sense of how people talked and what words were and were not in usage. I read newspapers of the time and other contemporaneous sources. For verisimilitude I added some words or phrases that were peculiar to the period.

I discovered a few books that provided information about terminology of earlier periods:

- Maurine Harris and Glen Harris. Concise Genealogical Dictionary. Provo, UT: Ancestry, 1998.

- Paul Drake. What Did They Mean by That: A Dictionary of Historical Terms for Genealogists. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 1994.

Historical societies have voluminous resources: old maps, directories, and government documents. I interviewed the foremost expert on the life of May Dugas in Menominee, Janet Callow, who I tracked down through the Menominee Historical Society. I also spent a day at the New York Historical Society and found many helpful materials, including maps that showed street layouts in the early 1900s. Other local resources also served me well. For instance, I discovered that the New York City Library has a collection of genealogical and historical information on the city, as well as early photographs.

I found the internet most helpful for researching highly specific, obscure, or idiosyncratic topics, for instance, salaries and the costs of goods during the period, when hotels started offering room service, and what heating systems could be found in homes then. Of course, I checked on authorship of the material. Monographs or dissertations are more reliable sources of information than those developed by amateur historians.

I soon learned it is absolutely essential to take notes on key material and its source. After reading a few dozen books it was difficult to remember exactly what I had read in the first dozen. Also, since I often needed to revisit a particular source later for additional or clarifying information I found a good recording system indispensable.

The historical novelist will never (and should never) use all the facts gleaned, but to be really knowledgeable the writer must always acquire more information than he or she would ever actually use. Research was half the fun!

![]()